Nostalgia for the Present. The Creative Union of Russian Artists. Moscow, 2020. ISBN 978-5-4386-2128-7

Russian Art in the New Millennium. Edward Lucie-Smith, Sergei Reviakin. London. 2022. ISBN 978-1-9134-9172-7

Museum of Self-Isolation, Museum of Moscow, Triumph gallery, Moscow, 2021. ISBN 978-5-6043738-1-1

Russian Nowhere. Pavel Otdelnov, Triumph gallery, Moscow, 2021. ISBN 978-5-6043737-7-4

CHA SHA, Catalogue of the exhibition, Jart gallery, 2021

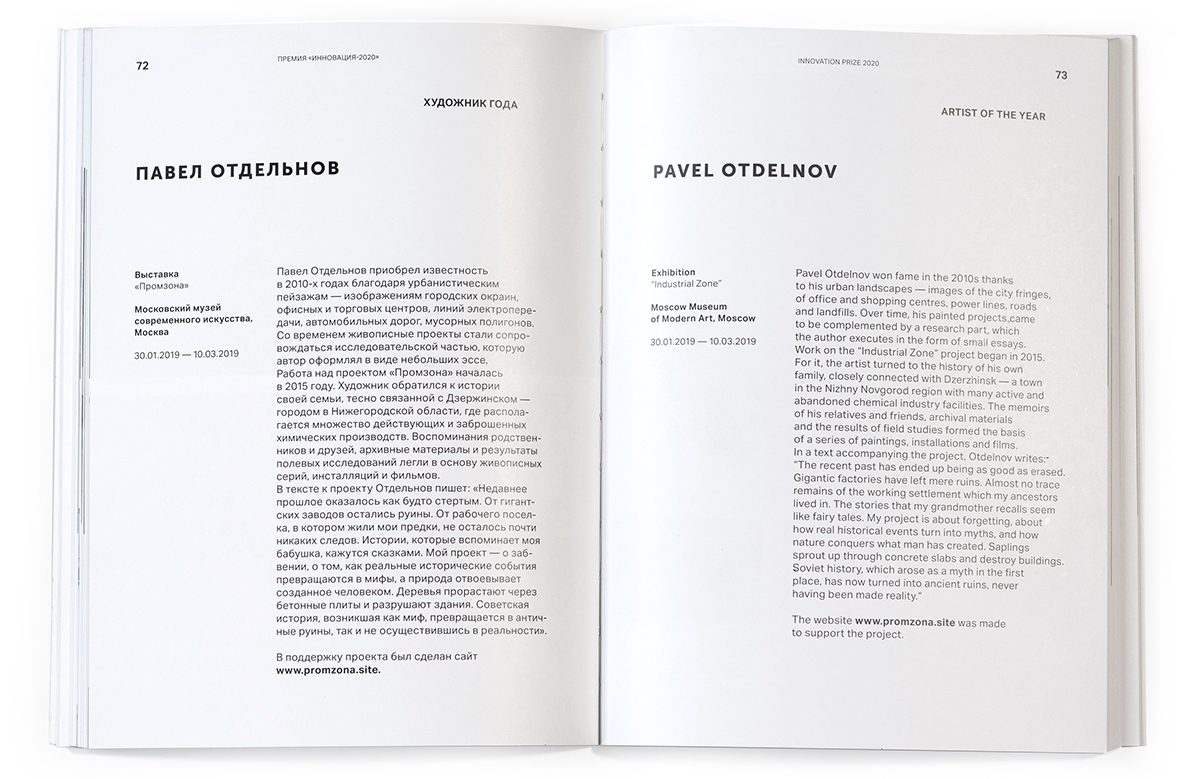

Innovation Prize, exhibition of the nominees catalogue. Nizny Novgorod, 2020

Promzona. Pavel Otdelnov, Triumph gallery, Moscow, 2019. ISBN 978-5-6041668-8-8

Critical Zones. Observatories for Earthly Politics, Bruno Latour and Peter Weibel, the article "Trajectories of Modernization in Russia: Artists Recalibrating the Sensorium" by Daria Mille. Zentrum für Kunst und Medien Karlsruhe, MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2020. ISBN 9780262044455

Generation XXI. The gift from Vladimir Smirnov and Konstantin Sorokin, The State Tretyakov gallery, Moscow. 2020. ISBN 978-5-6044419-0-9

State of Emergency, catalogue for the exhibition, Triumph gallery, Moscow. 2020. ISBN 978-5-6043051-7-1

Metageography: towards the new politics of geographical imagination, Zarya Centre for Contemporary Art, Vladivostok

Offline/Online, catalogue for the exhibition, DK Gromov, Saint Petersburg, 2019. ISBN 978-5-4386-1806-5

Kandinsky Art Prize. Catalogue of the exhibition, BREUS Foundation, Moscow, 2019. ISBN 978-5-6040802-5-2

NEMOSKVA. Big Country — Big Ideas, Moscow, 2019

Russia. Realism of the XXI century, Palace Editions, The State Russian Museum, Saint Petersburg, 2018. ISBN 978-5-93332-624-3

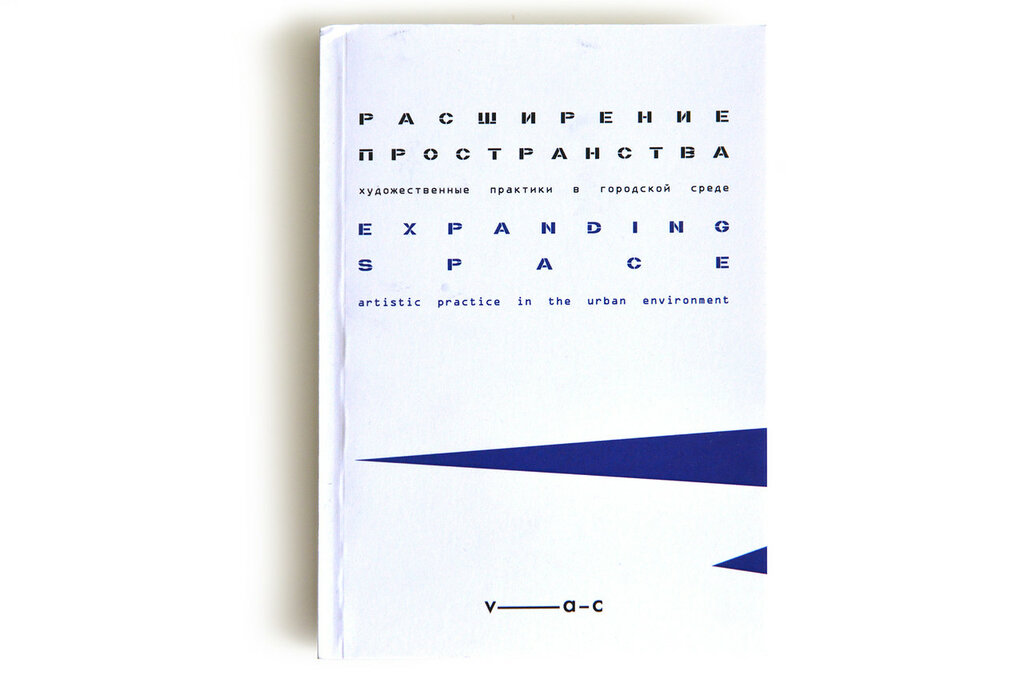

Expanding space, V–A–C press, Moscow, 2018. ISBN 975-5-9909519-4-5

At the Fringes, Department of Research Arts, Moscow, 2018. ISBN 978-5-6041668-0-2

The Arrival of a Train, catalogue for the exhibition, The Ekaterina Cultural Foundation, Moscow, 2018

Moscow — Kazan — Moscow, Department of Research Arts, Москва, 2018. ISBN 9785604073032

Contemporary art, Jart gallery, Moscow, 2018

Catalogue of the 4th Ural Biennal of Contemporary Art "New Literacy", Ekaterinburg, 2017. ISBN 978-5-7996-2244-2

Come back home, catalogue for the exhibition, Institute of Russian Realist Art, Moscow, 2017. ISBN 978–5–9909260–1–1

Sergey Kuryokhin Contemporary Art Award 2016, Kuryokhin Center, St. Petersburg 2017

Catalogue of the 5th Moscow Biennal of Young Art "Deep Inside", Moscow, 2016. ISBN 978-5-94620-111-7

Spaces of the sight. Art of 2000 — 2010. Articles, Konstantin Zatsepin, Samara, 2016. ISBN 978-5-9909189-4-8

Metageography. Space — Image — Action, catalogue for the exhibition, The State Tretyakov gallery, Moscow, 2016. ISBN 978-5-906550-47-7

Internal modernism, catalogue for the exhibition, GROUND Peschanaya, Moscow, 2016

Mall. Pavel Otdelnov, catalogue of the exhibition, Triumph gallery, Moscow, 2015. ISBN 978-5-906550-56-9

No Time, catalogue for the exhibition, Centre for Contemporary Art Winzavod, Moscow, 2015

Russia. Realism. XXI century, Palace Editions, The State Russian Museum, Saint Petersburg, 2015. ISBN 978-5-93332-528-4

Desolation of landscape, project of the DI art magazine, catalogue for the exhibition, 2014

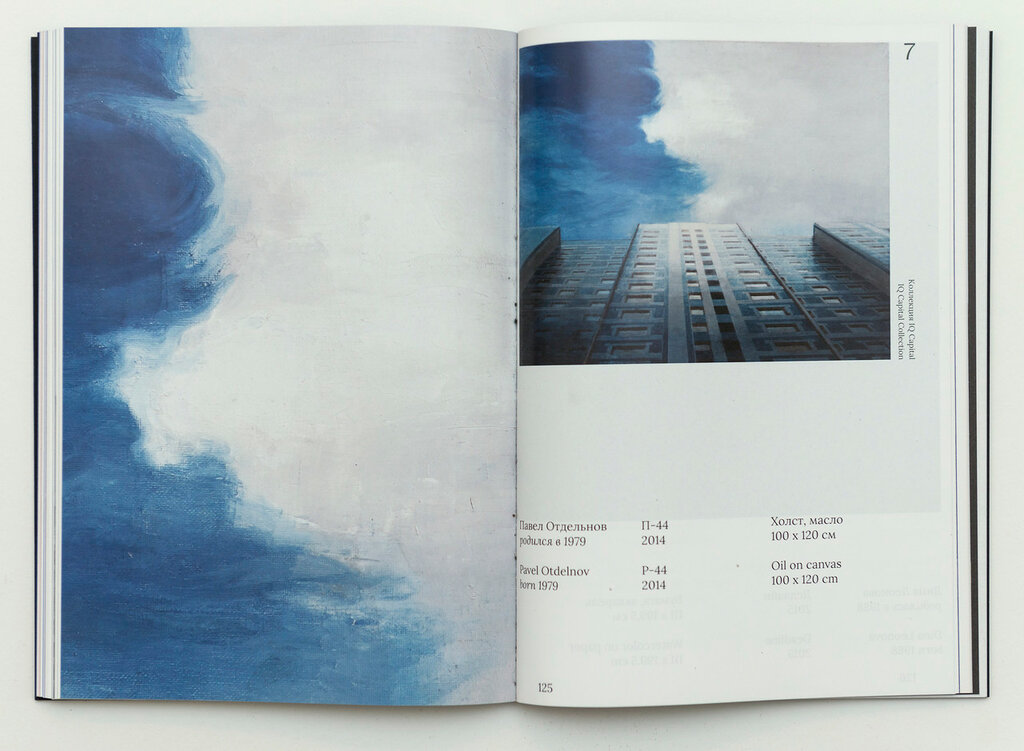

Internal Degunino. Pavel Otdelnov, catalogue of the exhibition, Moscow Museum of Modern Art, with the support of Triumph gallery, Moscow, 2014

Catalogue of the 4th Moscow Biennal of Young Art "Time to Dream", Moscow, 2014. ISBN 978-5-94620-095-0

Neon landscape, catalogue of the exhibition, Art.ru agency, Moscow, 2012

Combine. Retrospective, catalogue of the exhibition, Heritage gallery, Moscow, 2012

Kovcheg gallery. Postwar and Contemporary Art, Moscow, 2011

Russian Nowhere. Pavel Otdelnov, Triumph gallery, Moscow, 2021. ISBN 978-5-6043737-7-4

|

The new exhibition by Pavel Otdelnov, symbolically titled Russian Nowhere, makes a mesmerising impression, in a way evocative of David Lynch movies. Trying to articulate its aftereffect on the viewer, which does not quite lend itself to verbalisation, it can be argued that the “enigmatic landscapes”1 on display are a paradoxical combination of extreme defamiliarisation and materiality, on the one hand, and superhuman tenderness that ventures into mysticism, on the other. The new series by the artist revisits the subject of “non-places”2 and continues the deep exploration of our collective unconscious by focusing on urban marginalia. This time, however, the poetics of non-places is enriched by an infusion of virtual imagery. The term “non-place” was originally coined in art criticism by the founder of land art Robert Smithson, and it has been used to denote the zones, produced by the urban civilisation, that are occupied for short periods of time and anonymously, and that erase personal identity. In philosophy, as introduced by Michel Foucault, such places are termed “heterotopia”, from the Ancient Greek for “other” and “place”. A place is identified here through a differentiating, special mode of life and a special chronotope. Endless casemates of garages, deserted highways going nowhere, industrial estates, road junctions and other “disowned spaces” in the urban outskirts of Russian Nowhere — all that can await us around any corner in our familiar daily routes (“I thought it was a painting, but this is life”) — these are examples of heterotopias with their particular aesthetic and space-time configuration. The heterotopias / non-places in Pavel Otdelnov’s new series are so well known to everybody who lives in Russia that they unfailingly produce an effect of stark déjà vu, which reveals the eternally Russian “it’s the same everywhere”. Back in 1951, at a Darmstadt conference, Martin Heidegger made a presentation “Building, Dwelling, Thinking” on a bridge construction project, where he argued that the identity of a place emerged from both its objective spatial parameters and from the eye of the beholder. When presented with the heterotopias in Pavel Otdelnov’s new series, the question of that eye immediately comes to mind, which can, once answered, serve as the key to the world of Russian Nowhere. The seminal question posed by Michael Foucault “who is speaking?”, as applied to visual arts, should be restated as “who is looking?” Whereas the past series by Pavel Otdelnov offered a most sympathetic view on the depicted non-places that can be attributed as a view of a person in the future3, in case of Russian Nowhere such perspective is no longer possible: Enthusiasts Street now leads nowhere, and the monolith concrete fence spanning over the entire horizon bears the inscription: “The future has never come”. In Russian Nowhere, Pavel Otdelnov has aptly captured this recently emergent phenomenon in the collective sensibility of dealing with the loss of the future as a human project. A person is not a personal project anymore, the person has now denounced the myths, which used to hold power over us, of being the architects of our own futures. The initiative now lies with non-human actors: the natural entropy that prevails and erases from the face of the earth the remains of grand social utopias, the onslaught of new deadly viruses brought about by the environmental disaster, the menacing self-animation of technology. Even if the future were to present itself today, this would be through personalised eschatology (“Russia is the land of fascinating wonder: Start your life here, and it all goes under”). So whose eye is it, contemplating the dehumanised space with such |

defamiliarisation and distance as if from a bird’s eye view? Might this be a machine eye? Indeed, the optics used in Russian Nowhere is on principle that of a machine: both in the photographs and in the paintings of this series, there is no need for human presence in the landscapes captured by dispassionate machine vision. The artistic gesture — newly introduced here by the author and amplifying the already existing defamiliarisation effect — consists in painting the canvases from images found on street view by Yandex and Google, and in recreating a painterly image from that; this takes to the extreme the themes of dehumanisation of the depicted space and of the subject’s death in art. The artist himself calls this technique the “principle of simulated remote view”. If this is a machine looking, though, why do we get a persistent anxious apprehension from these landscapes, as if something unseen is lurking behind the seen, as if something has happened or is just about to? Why the presence of vibrating sadness, piercing nostalgia, phantom pains over the era long gone and the man dissolved in these dehumanised landscapes? Over the paintings missing the shadows of people once living, building, dreaming here, whose dreams were turned to dust and faded into oblivion. Or over those who, continuing to dwell in the drab non-places, in the dimensionless faceless spaces of the Soviet (Russian?) Atlantis, which is submerging underground and under tonnes of compressed time right before our eyes, are also becoming invisible, turning on Otdelnov’s canvases into barely distinguishable marks, an empty sign of a person, a ghost. This is no human view: a person in the space of Russian Nowhere is dematerialised (their palpable absence gives a powerful impetus to imagination). Neither is the view that of a machine. Machines have no nostalgia, and the world does not present itself to them as presence. Still, whose eye could be looking at the lands in Pavel Otdelnov’s Nowhere? The one looking at these monotonous, almost fully devoid of colour, literally in-congruous landscapes (“there is no aesthetic in it”) could be one of the Wim Wenders’s angels from Wings of Desire (1987), Cassiel, whose original purpose was to observe, witness and keep record of reality. Or Wenders’s other angel, Damiel, who is sympathetic to the people on earth and appreciates this flawed world so much that he becomes willing to give up his immortality in order to see it through the mortal’s eyes or, say, experience a “mixture of sadness, nostalgia, romanticism and, probably, hopelessness”, as relayed in one of the anonymous sentiments that Pavel Otdelnov has retrieved literally from our collective unconscious — from the social media. His series of photographs is poetic in its precise use of verbatim quotations from recurring comments in social media communities focused on the “aesthetic of gloomy nowhere”, or, to cut through the euphemisms, on the ruination of Russia4. Ruins are definitely featured among the repetitive structures in Pavel Otdenov’s work. In his artistic world, ruins are not so much a representation of past events as, rather, a hint at the impossibility of such representation, at the contained isolation of past experience from us. Although its progressively disappearing traces are still present, the past is not meaningfully perceived by us, which makes it simultaneously horrific and alluring. Yet, taking a different angle, the non-places — that, despite of all of the above, Pavel Otdelnov makes us admire by virtue of the magical power of art — might be that last haven where the vestiges of humanity can find rescue from the glossy terror of simulated reality. And where amidst the voiceless deserted middle of nowhere, with its invariably grey skies and washed-out lighting, it is the only remaining place to, perhaps, encounter an angel. Svetlana Polyakova |

1 Zatsepin K. A. “Enigmatichesky Peizazh” [Enigmatic Landscape] // Prostranstvo Vzglyada. Iskusstvo 2000–2010kh Godov [The Space of Vision. Art of the 2000–2010s]. In Russian. Collection of essays. Samara: Knizhnoe Izdatelstvo, 2016

2 Editor’s note: as used in several humanitarian disciplines, the term “nonplace” has different forms in both Russian and English. The variant “nonplace” is typical of Robert Smithson’s artistic concept, which is discussed further in the text, typical of culturology (e.g., see Symbolic Exchange and Death by Jean Baudrillard), and of anthropology (e.g., see Non-Places: Introduction to an Anthropology of Supermodernity by Marc Augé). Another variant, “nonplace”, is current in studies of utopias and in urban studies (e.g., Yury Saprykin’s writings). Note, however, that the Russian academic and journalistic discourse is yet to settle on an established usage on this term, and it may have different meanings depending on the context.

3 See Polyakova S.V. “Ne-mesto v Iskusstve i v Postchelovecheskom Mire” [Non-place in Art and in the Post-Human World] // Dialog Iskusstv [Dialogue of Arts]. In Russian. 2017. No. 4.

4 The phrases used in these works take on an additional layer of meaning when one learns that the red lettering was made to order by the same company that manufactures signs for such outskirt regulars as construction supply markets or Pyaterochka, a value grocery chain.

CHA SHA, Catalogue of the exhibition, Jart gallery, 2021

Innovation Prize, exhibition of the nominees catalogue. Nizny Novgorod, 2020

Promzona. Pavel Otdelnov, Triumph gallery, Moscow, 2019. ISBN 978-5-6041668-8-8

"Critical Zones. Observatories for Earthly Politics", Bruno Latour and Peter Weibel, the article "Trajectories of Modernization in Russia: Artists Recalibrating the Sensorium" by Daria Mille. Zentrum für Kunst und Medien Karlsruhe, MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2020. ISBN 9780262044455 pp. 378-379

|

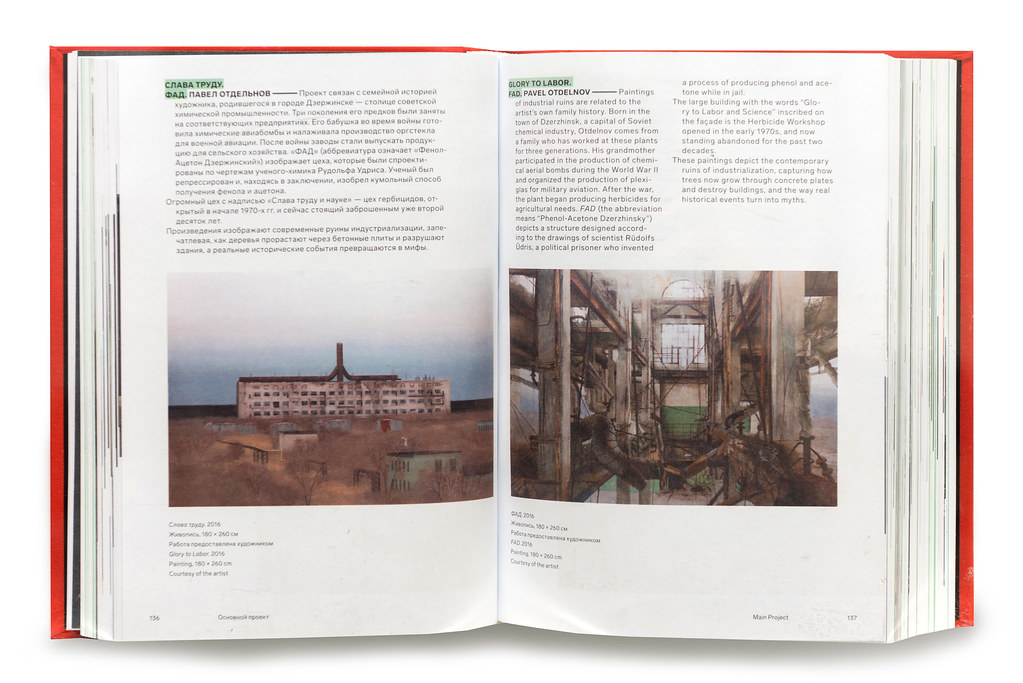

A growing awareness in Russian society and among artists regarding the legacy of the Soviet modernization project is also seen through the interest in “microhistories.” These are testimonies narrated by ordinary people, and by contemporaries from their families. Thus, step-by-step, the collective past is starting to be shaped, bringing another scale and temporality to the questions of how humans intervene in the Critical Zone and inhabit the territory. This approach makes it possible to show the entanglement of the individual in the vast context of ecologic devastation left by the modernization project of the twentieth century, which is therefore realized to be part of collective memory. The arts-based research by Pavel Otdelnov is a part of this tendency. In his recent projects shown collectively in the exhi- bition Promzona (2019) at the Moscow Museum of Modern Art, he tells the story of the chemical plants in his native city of Dzerzhinsk (Nizhny Novgorod region). In the Soviet era, it was the largest center of the chemical industry, a city of scientific triumphs and progress, producing large quantities of chemical weapons. Its importance has faded away as did the utopian ideology, leaving behind a territory on the verge of environmental disaster caused by both legal and illegal unsafe disposal of toxic chemical waste. According to the Blacksmith Institute, this is one of the most polluted places in the world. What can be seen today are large areas of wastelands, chemical waste reservoirs, and ruins that are being reconquered by flora and fauna. While preparing his projects, Otdelnov studied the territory of the chemical plants, various archival materials, contemporary newspapers, and personal stories of people who used to work in the chemical industry. |

The history of the artist’s family became the starting point of his research. Three generations of his ancestors worked for the chemical industry in Dzerzhinsk, and witnessed the development of the plants over the city’s history. The films From White Sea to Black Hole (2019; the title refers to the color of the polluted territories) and Chemical Factory (2019), both shot from a quadrocopter, reveal picturesque views of the territories polluted by the former chemical plants. The perspectives of the images create ambiguities of scales, of being on macro or microlevels. The films show the surface of the Earth, its polluted skin, as though it is a view of an unknown, strangely beautiful planet. These contemporary aerial views combined with the presentation of the historical objects from these areas (staged as a local history museum) and stories of people who had lived there about their sense of this place (film Subjects of Memory, 2016) create a strange feeling as though the alienated territory were being brought back and you have yet to settle on this strange alienated ground that is also your Heimat [home]. In his artistic works Otdelnov creates a very special sense for a place that is exposed to “slow violence” and is recognizable without having a particular name or geographic location, a landscape haunted by its past and imagined utopian future. It is not just one tragic personal story of environmental devastation in a particular place that is being recognized here, but an image of the common past — an epoch of progress and modernization, of huge (secret) industries, which we still have to learn a lot about in order to find a balance for coexistence within the Critical Zone. Daria Mille. Trajectories of Modernization in Russia: Artists Recalibrating the Sensorium. Critical Zones. Observatories for Earthly Politics |

Catalogue of the 4th Ural Biennal of Contemporary Art New Literacy, Ekaterinburg, 2017. ISBN 978-5-7996-2244-2

Catalog for the exhibition Moscow – Kazan – Moscow, Department of Research Arts, 2018. ISBN 9785604073032

Book by Konstantin Zatsepin The space of the sight. The Art of 2000–2010. The Digest of Articles – Samara, Book Edition, 2016, 120p. ISBN 978-5-9909189-4-8

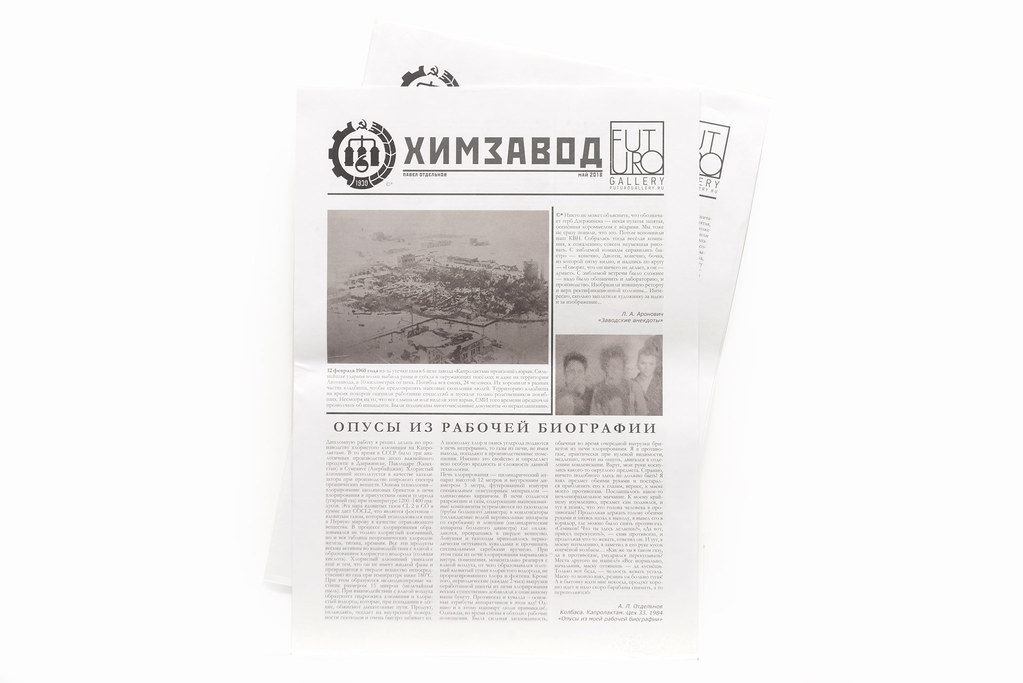

Newspaper for the exhibition Chemical Plant, FUTURO gallery, Nizhny Novgorod, 2018

Postcards for the exhibition Chemical Plant, FUTURO gallery, Nizhny Novgorod, 2018

Guide for the exhibition White sea. Black hole. NCCA Arsenal, Nizhny Novgorod, 2016

Catalog for the exhibition Metageography. Space – Image – Action, The State Tretyakov gallery, Moscow, 2015

Catalog of the Sergey Kuryokhin Contemporary Art Award 2016, Kuryokhin Center, St. Petersburg, 2017

Catalog for the exhibition Come Back Home, Institute of Russian Realist Art, June, 10 – September, 10, 2017

ISBN 978–5–9909260–1–1

Catalog for the exhibition Mall, Triumph gallery, November, 12 – December, 6, 2015

|

In the late 1950s-early 1960s Yury Pimenov, who had until then created canonical images of the industrial landscape of the 1920s (You give heavy industry! ) and Stalinist glamour (New Moscow ), painted several canvases to inaugurate the birth of a new urban environment. The District of Tomorrow, Marriage on the Streets of Tomorrow, The First Fashion Ladies of the New District glorify Khrushchev’s new prefabricated residential districts, against the backdrop of a sky blackened by the gib arms of building cranes and the stacks of concrete pipes on which they run sportily on their heels in brightly fluttering dresses, future husband and wife, parading directly on wooden bridges laid down in the dirt. At exactly the same time Dmitry Shostakovich was writing his own operetta Moscow.Cheremushki , which was shortly thereafter adapted in a screen version, glorifying the new housing developments as an opportunity to break away from the musty old world of communal flats to a new life — ascetic, free (the so-called “Khrushchevka” flats ensured privacy), desperately young, modern and even international. In Herbert Rappoport’s musical (born in Vienna and until his emigration to the USSR in 1936 the former assistant of Georg Pabst with whom he had worked in Germany and in Hollywood), they parody West Side Story and dance rock and roll directly on the panel of the house being built suspended on the crane. In the case of Shostakovich, Pimenov and Rappoport, people from the first avant-garde generation, the new housing developments of the thaw era marked a return to modernism, an appeal not to the mythical past or the eternal present as in the Stalinist Empire style, but rather to the future, at the time mentioned in the names of Pimenov’s canvases - Tomorrow , a time that has still not arrived, but will definitely come — so that one can for the time being endure patiently temporary inconveniences, the chaos of the establishment of the new and the dirt, which is presented in Pimenov’s pictures as sign of the organic vitality of the new world being built. The romantic halo that surrounded the new developments in the thaw years had definitively melted away by the onset of the stagnation era of Brezhnev. The typical suburban high-rise buildings became a standard form of alienation — whether it be the surprisingly depressing romantic comedy The Irony of Fate as the country’s main New Year story, or the desperately existential drama Vacation in September, or the paintings of domestic photo realists, who sought incidentally, through “branded”, “western” picturesque textures, to transform the “Russian distemper” into something akin to “English spleen”. In principle, the high rises of the Khrushchev-Brezhnev eras deserved the fate of the Pruitt-Igoe residential complex in Saint Louis that was so similar to them. The high-rises built in 1956 were transformed from a rational utopia into ghetto housing that was so uninhabitable that they were blown up in 1972. As we know, for American architect and art historian Charles Jencks this was the date of the death of modernism and the birth of post-modernism in architecture. In the case of Pavel Otdelnov, who has already studied for several years in his paintings the aesthetics of Moscow’s commuter districts, post-Soviet post-modernism in architecture, if there has been any, is represented not by Luzhkov’s towers, but rather by the shopping centres in suburbs, growing in amongst perennial Brezhnev residential districts and waste lands. Following the appearance of these structures in the typically grey architectural landscape, at least some colours have appeared. The acidic, eye-grabbing colours of the shopping centres turn them into mock buildings, and even giant toys. The bright local colours introduced in the architecture might also have inspired the authors of De Stijl to come up with Montessori educational toys. However, naturally there are no didactic aspirations in the toy nature of |

Moscow’s suburban moles. It is highly likely that the builders, who had decided to do something appealing to visitors, had been overcome by the same babbling and obsequious tone as advertisers and the compilers of menus, who abused diminutives, appealing to our infantile nature.Incidentally, in Pavel Otdelnov’s canvases, the shopping centre are devoid of people — their interiors are reminiscent of neglected space stations of unknown civilisations, while their multicoloured 3D boxes on stale wastelands rendered them more similar to huge sculptures than buildings that you can climb into. In the new cycle they definitively devolve into mirages. There are no longer any buildings — the inappropriately bright colours stand out in the primordial greyness of suburbs as a glitch, a digital malfunction, a suspended “matrix”. At the time of their disappearance, these phantoms looks particularly resplendent — laser shows, the gaudy fairy show of Las Vegas. However, they are so ephemeral that they are not even reflected in the eternal puddles of the suburban wastelands. In the case of Pavel Otdelnov, who has already studied for several years in his paintings the aesthetics of Moscow’s commuter districts, post-Soviet post-modernism in architecture, if there has been any, is represented not by Luzhkov’s towers, but rather by the shopping centres in suburbs, growing in amongst perennial Brezhnev residential districts and waste lands. Following the appearance of these structures in the typically grey architectural landscape, at least some colours have appeared. The acidic, eye-grabbing colours of the shopping centres turn them into mock buildings, and even giant toys. The bright local colours introduced in the architecture might also have inspired the authors of De Stijl to come up with Montessori educational toys. However, naturally there are no didactic aspirations in the toy nature of Moscow’s suburban moles. It is highly likely that the builders, who had decided to do something appealing to visitors, had been overcome by the same babbling and obsequious tone as advertisers and the compilers of menus, who abused diminutives, appealing to our infantile nature. Incidentally, in Pavel Otdelnov’s canvases, the shopping centre are devoid of people — their interiors are reminiscent of neglected space stations of unknown civilisations, while their multicoloured 3D boxes on stale wastelands rendered them more similar to huge sculptures than buildings that you can climb into. In the new cycle they definitively devolve into mirages. There are no longer any buildings — the inappropriately bright colours stand out in the primordial greyness of suburbs as a glitch, a digital malfunction, a suspended “matrix”. At the time of their disappearance, these phantoms looks particularly resplendent — laser shows, the gaudy fairy show of Las Vegas. However, they are so ephemeral that they are not even reflected in the eternal puddles of the suburban wastelands. Pavel Otdelnov’s new project would appear extremely topical today when the joys of the consumer society and hopes for some cultivation of the local social and living space are bursting like soap bubbles. Carefree post-modernism did not come to pass. The motley cubes of the toy buildings remain like a computer model imposed on the colourless landscape of the commuter districts, which have not stirred from their sleep, on waste lands built by the fortresses of the residential districts, which have not turned into cities, while the slush waits in vain for the tomorrow that will transform it into a street. Furthermore, it transpires that new technologies or state-of-the-art trends do not provide the most appropriate language to describe this reality: rather, it is the figurative art that Pavel Otdelnov studied at V. Surikov Moscow State Academy Art Institute, at the studio of one of the founding fathers of Pavel Nikonov’s “austere style”. Irina Kulik |

Expanding Space, book V–A–C press, 2018, ISBN 975-5-9909519-4-5

Catalog for the exhibition of public-art projects Expanding Space, V–A–C foundation, 2015

Mall. Glitch

|

Bright shopping mails, standing out against the background of the surrounding bedroom districts and industrial estates, have dramatically changed the city's face. Today they are not only a part of consumer culture, but a symbol of the first decade of the 2000s. |

The Mall. Glitch project is a kind of a monument to the "colourful hangars" epoch, the period of stability. Today in many cities you can already find abandoned or unfinished trade centers. The exhibition presents a 3D visualization of the object. |

Catalog for the exhibition No Time, Smirnov & Sorokin foundation, Winzavod, 2015

Catalog for the exhibition Russia. Realism. ХХI century, The State Russian Museum, 2015–2016

Catalog for the exhibition Desolation of Landscape, Moscow – Saint-Petersburg – Usol'e, "Dialogue of Arts" magasine, 2014 – 2015

Catalog for the exhibition Inner Degunino, MMOMA, with the support of Triumph gallery, 2014

|

Pavel Otdelnov’s Inner Degunino is a project, prepared specially for the youth program of Moscow Museum of Modern Art.Exhibitions of the program have been hosted by the MMOMA since 2006. Over the years, works by many interesting artists, using different techniques, have been exhibited. We presented artists, engaged in photography, video, object and installation art, painting and media performance. In recent years, there has been a tendency of return of painting in the context of the latest trends of contemporary art. More and more interesting young artists turn to painting as a medium, which has a great visual potential and a rich cultural background. The Internal Degunino project is a good example of the artist’s use of the language of painting to solve his artistic and conceptual tasks. The project arouses a painful feeling of vast empty spaces of the city suburbs. As if someone creates a 1:1 scale-model of the city, collecting some elements of standard parts, but it is not still ready. The flat landscape covered with the grey urban snow together with residential areas creates the illusion of abandonment of alien objects, which serve as a shelter for the night and happiness of tens of thousands of people. |

As if seen blurred vision, elements of the urban landscape transform into symbols of themselves, emerging from obscurity for a moment and disappearing again as soon as the viewer changes his gaze direction. Fixing of the ordinary was characteristic of the culture of the 2nd half of the 20th century. In the 1950s, praising objects, produced by mass culture, the Pop art introduced the profane in the language of art. In the late 1960s, the Hyperrealism captured the ordinary in great detail, and Gerhard Richter painted his “blurry photos”. The ordinary, familiar, banal became a legitimate part of the contemporary visual culture. The characters of Pavel Otdelnov’s paintings are subway passengers or P44 series panel buildings, or bright shopping centers. The artist seems to recreate the period of stagnation in the life of an urban inhabitant, the moment of his travels over the conventional West Degunino district, when surrounding real objects are scenery for teleportation to a tiny cell of the life with a sofa, dinner and a TV rather than a part of the life. Every day millions of people pass this way, followed by power lines, and erase it from their life, treating it as a period of meaningless solitude. Daria Kamyshnikova |

Catalog for the exhibition of the main project A Time for Dreams, the 4th International Biennale of Young Art, 2014

Catalog for the exhibition Neon Landscape, ArtRu Agency, 2012

Comfort Zone

Paintings by Pavel Otdelnov

|

Neon in the history of material culture is connected to the notions of economy and movement. It is widely believed that the first neon sign in America was installed in California in 1922 and served as a sign for a car dealer. Artificial light based on inert gases from the atmosphere accompanies us on our route from the start – the railway station, the airport – to the finish, that is to say, another airport and station. Unlike natural light or a candle's dancing flame, this kind of light is constant and invariable. It is either on or something isn't right. Neon is also a stop on our way: the brighter the sign, the bigger the chance to halt the traveler's movement, because illumination equals security. A blinking daylight in a subway passage is cinematic cliché that serves as a marker of poor social conditions of the scene or gives the unseen threat seconds of darkness to form and strike. Bright city lights can be perceived as a sign of cheapness. Edward Hopper's “Nighthawks” (1942) hide their faces and shrink like moths on a light bulb. Neon's stable brightness forms the space of forced equality in public spaces of different functions, malls to prisons. Neon organizes people into masses. It turns personal dramas into embarassing signs of weakness. Intimacy is possible under the artificial light, but it has to be subdued by a dispersal surface like glass or cloth. Hopper's protagonists often look constrained, inert like gas, unable to enter each other's space. People on Pavel Otdelnov's paintings also can not be considered an active bunch, but they are not the center of attention. Otdelnov treats artifical light as a pattern that brings order and rationality to the real world, “giving us back the Euclidian space”, as he says. Empty spaces, where light does not tread, are places where the electric signal's lost. The painting turns into an object, a flat piece of canvas conversing with other things around. Here it also vibrates and projects natural light of paint outside. |

These areas of painting have depth that cannot be calibrated. Archaic remembrances of earth and subconsciousness abound, the painting becomes truly hand-made, independent from artificial light. Borders between light and a living, breathing plane are movable. In some paintings the light is slowly stripped of its architectural role, in others it stops abruptly. Men and women on stations and in trains are staffage in an ideal box that is painted by light. Sometimes humans disperse, as in “Local train”, reminding one of taking long exposure photos where moving objects leave but a trace of light. In Charles Demuth's “I saw the figure five in gold” (1928) a sparkling sign leaps out of futuristic space divided in dynamic blocks. It has none of the awkwardness that is often a feature of Hopper's interiors. Demuth shows no people, but his painting is a metaphorical portrait of William Carlos Williams and is based on a line from Williams' poem. A human being is constructed from neon lights and moving numbers. Personality in a psychological sense is no longer there, giving in to the gaze that is free to construct urban space according to individual logic. This is a gesture of freedom that is not sympathetic to discussions of dehumanization of the industrial world. Otdelnov in his turn treats artificial light with sympathy, though the artist is heavily inspired by Gaspar Noe's movies like “Irreversible” and “Enter the void”. In Noe's tales the light plays a constantly sinister role in the unfolding of events. In Otdelnov's paintings even Scandinavian railway stations do not look creepy. His unseen protagonist is happy to see the light because he feels the comfortable comprehensibility of a world patterned by nets of lamps. Physical presence fades into background with all inconveniences it entails. Constant movement swallows self-reflection and protects both the artist and the viewer from loneliness. Valentin Diaconov |

Catalog for the exhibition Combine.Retrospective, Heritage gallery, 2012

Kovcheg gallery. Postwar and Contemporary Art. 2010

Catalog for the exhibition Overcoming Space, Kuznetsky most, 11, 2012