Comfort Zone

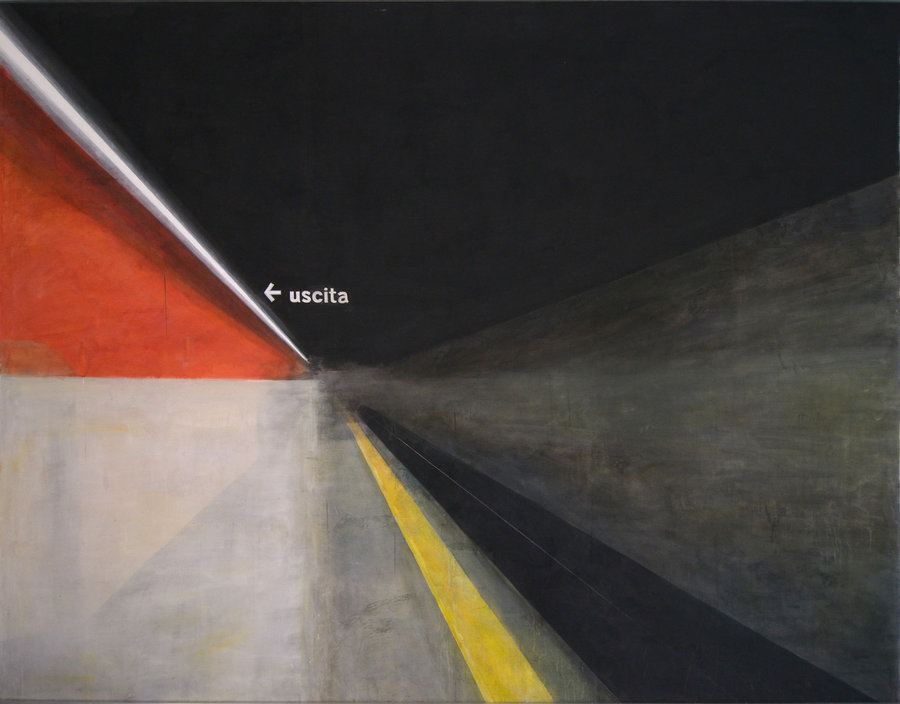

Paintings by Pavel Otdelnov

|

Neon in the history of material culture is connected to the notions of economy and movement. It is widely believed that the first neon sign in America was installed in California in 1922 and served as a sign for a car dealer. Artificial light based on inert gases from the atmosphere accompanies us on our route from the start – the railway station, the airport – to the finish, that is to say, another airport and station. Unlike natural light or a candle's dancing flame, this kind of light is constant and invariable. It is either on or something isn't right. Neon is also a stop on our way: the brighter the sign, the bigger the chance to halt the traveler's movement, because illumination equals security. A blinking daylight in a subway passage is cinematic cliché that serves as a marker of poor social conditions of the scene or gives the unseen threat seconds of darkness to form and strike. Bright city lights can be perceived as a sign of cheapness. Edward Hopper's “Nighthawks” (1942) hide their faces and shrink like moths on a light bulb. Neon's stable brightness forms the space of forced equality in public spaces of different functions, malls to prisons. Neon organizes people into masses. It turns personal dramas into embarassing signs of weakness. Intimacy is possible under the artificial light, but it has to be subdued by a dispersal surface like glass or cloth. Hopper's protagonists often look constrained, inert like gas, unable to enter each other's space. People on Pavel Otdelnov's paintings also can not be considered an active bunch, but they are not the center of attention. Otdelnov treats artifical light as a pattern that brings order and rationality to the real world, “giving us back the Euclidian space”, as he says. Empty spaces, where light does not tread, are places where the electric signal's lost. The painting turns into an object, a flat piece of canvas conversing with other things around. Here it also vibrates and projects natural light of paint outside. |

These areas of painting have depth that cannot be calibrated. Archaic remembrances of earth and subconsciousness abound, the painting becomes truly hand-made, independent from artificial light. Borders between light and a living, breathing plane are movable. In some paintings the light is slowly stripped of its architectural role, in others it stops abruptly. Men and women on stations and in trains are staffage in an ideal box that is painted by light. Sometimes humans disperse, as in “Local train”, reminding one of taking long exposure photos where moving objects leave but a trace of light. In Charles Demuth's “I saw the figure five in gold” (1928) a sparkling sign leaps out of futuristic space divided in dynamic blocks. It has none of the awkwardness that is often a feature of Hopper's interiors. Demuth shows no people, but his painting is a metaphorical portrait of William Carlos Williams and is based on a line from Williams' poem. A human being is constructed from neon lights and moving numbers. Personality in a psychological sense is no longer there, giving in to the gaze that is free to construct urban space according to individual logic. This is a gesture of freedom that is not sympathetic to discussions of dehumanization of the industrial world. Otdelnov in his turn treats artificial light with sympathy, though the artist is heavily inspired by Gaspar Noe's movies like “Irreversible” and “Enter the void”. In Noe's tales the light plays a constantly sinister role in the unfolding of events. In Otdelnov's paintings even Scandinavian railway stations do not look creepy. His unseen protagonist is happy to see the light because he feels the comfortable comprehensibility of a world patterned by nets of lamps. Physical presence fades into background with all inconveniences it entails. Constant movement swallows self-reflection and protects both the artist and the viewer from loneliness. Valentin Diaconov |

Pavel Otdelnov. Uscita. 2012. mixed media. 240x290

Pavel Otdelnov. Walkway. 2012, oil on canvas. 140x180. The State Russian Museum

Pavel Otdelnov. Inside/Outside. 2012. oil on canvas. 95x195. The Foundation of Vladimir Smirnov and Konstantine Sorokin

Pavel Otdelnov. Horizontal motion. 2012. oil on canvas, 90x150. Private collection

Pavel Otdelnov. Horizontal motion 2. 2012. oil on panel. 50x60

Pavel Otdelnov. Eurostar. 2012. oil on pane. 50x60. Private collection

Pavel Otdelnov. City. 2012. oil on panel. 50x60. Private collection

Pavel Otdelnov. 7x faster. 2012. oil on canvas. 180x180. The Foundation of Vladimir Smirnov and Konstantine Sorokin

Pavel Otdelnov. Up. 2012. oil on canvas. 103x112. Private collection, USA

Pavel Otdelnov. Nightlight. 2012. oil on canvas. 103x112

Pavel Otdelnov. Light of headlights. 2012. oil on canvas. 103x112. Private collection

Pavel Otdelnov. Speed. 2012. oil on canvas, 103x112. Private collection

Pavel Otdelnov. Speed 2. 2012. oil on canvas, 103x112. STB Bank Corporate Art Collection, Moscow

Link to the catalog of the exhibition.

Virtual exhibition: