|

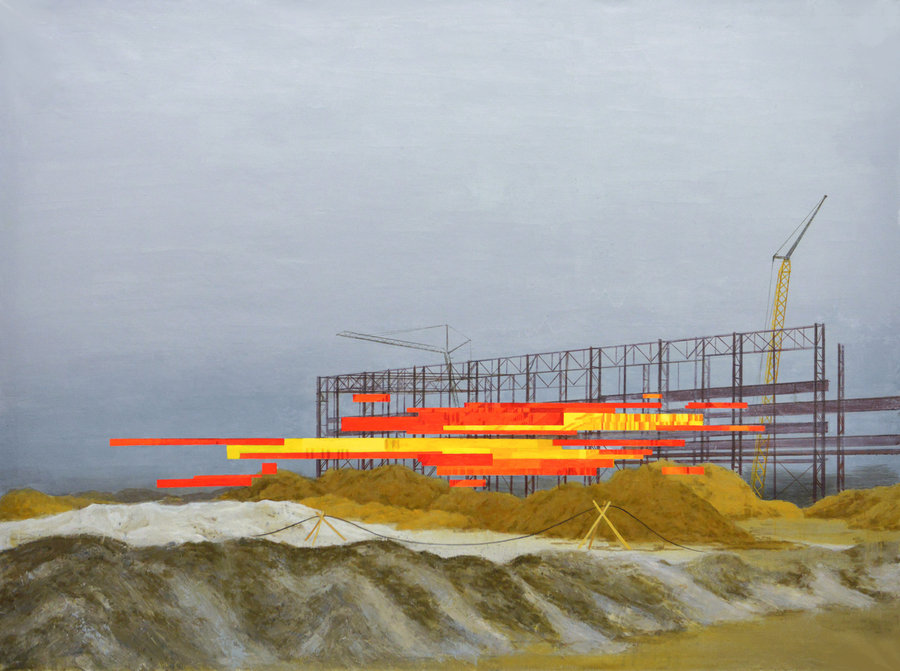

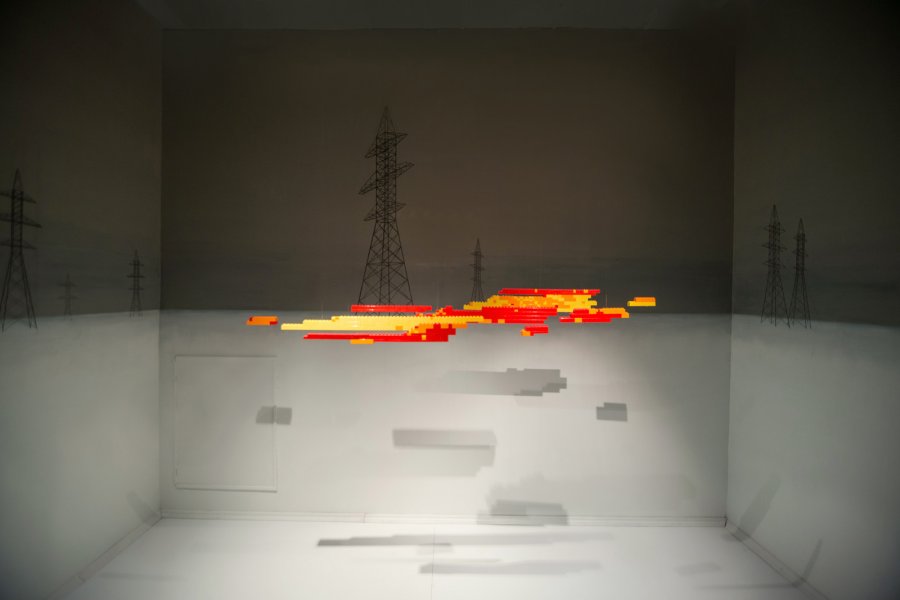

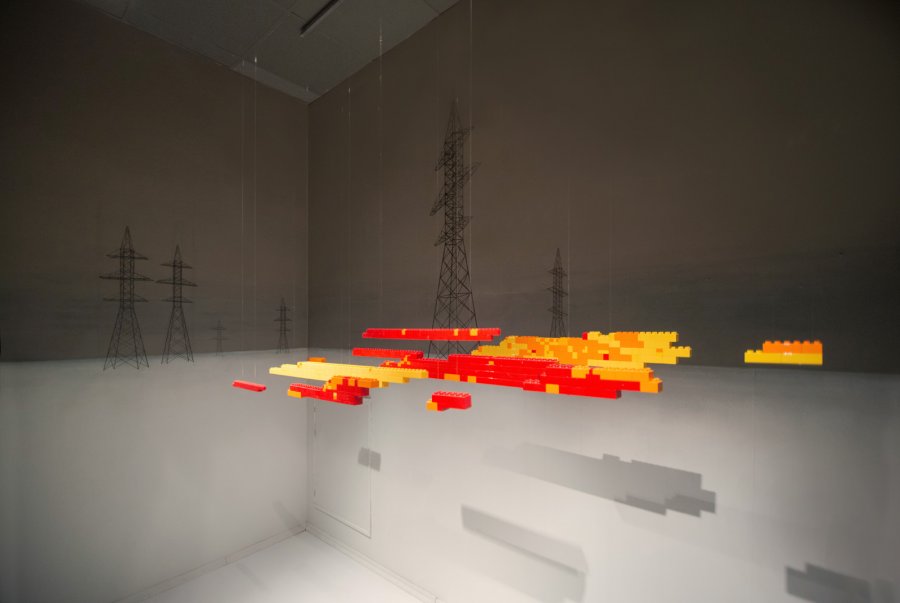

Malls represent one of the most important signs of our time. Over the past 10-15 years they have become the main venue for family leisure, and they dominate the urban landscape to such an extent that they cannot be ignored. A typical mall usually consists of a building that is absurd architecturally, builtrom non-permanent materials. It feels as if the architects of malls are primarily interested in the volume of the shopping areas and only to the last degree how these facilities will fit into the surrounding landscape. The more provocative they look, the better — this is how they achieve a greater contrast with the surrounding landscape and attract even more attention. And so multi-coloured sheds grow from plastic, composite panels and polycarbonate. These shopping complexes usually consist of a large number of shops, as leased retail space. The malls are frequently combined with transport, entertainment, and other service enterprises and institutions. The external walls of the malls frequently look as visual noise: they boast various advertising signboards, with each one seeking to shout down all the others. The vestiges of the Soviet era of modernisation — these are the powerlines, which embodied Lenin’s modernist dream of universal electrification and standard house construction — the facades of modular houses, and extensive industrial zones. We are accustomed to perceiving these aspects of the landscape as something stable, like the background. Against this background the construction of state-of-the-art shopping and entertainment infrastructure is emerging. Major shopping centres started appearing en masse in Europe and the USA in the 1950s, and in Russia and the post-Soviet space in the 2000s, and continue appearing to this very day, spreading from cities with a million-plus population to the periphery. These countless shopping and leisure centres turn up in close vicinity to commuter cities and industrial zones. They grow into the rationally planned city environment like wildfire. Such a shopping complex, which grew in the wide open spaces of our country among post-Soviet residential districts and garages, is reminiscent of a computer error, a software bug, or a glitch. One of the most typical reasons for the occurrence of glitches is the non-compliance of the software with the task set by the user. A mall as a glitch may be described as a metaphor of the non-compliance of post-Soviet social reality and the market relations of the emerging capitalist era. |

The glitch usually usually represents decay and stratification, it is dynamic and records the moment of transformation. If you view a typical mall through the prism of a time lapse, you can see how the bright signs come and go interchangeably and how the banners flicker, and such flickering is extremely reminiscent of a computer bug, The mall in the post-Soviet space could be described hypothetically as an instable phenomenon in a stable place. The activities of malls are highly dependent on the wellbeing and prosperity of the emerging “middle class”. In connection with the most recent economic events (crisis, sanctions, inflation), the mall is suffering serious losses. And now the first abandoned, unfinished malls are appearing in the Moscow suburbs, and we may subsequently see a wave of closures of such centres for shopping and cultural leisure. This dependence of malls on the economic situation and its collisions one can metaphorically describe as a software bug, permanent glitch. The activities of malls are highly dependent on the wellbeing and prosperity of the emerging “middle class”. In connection with the most recent economic events (crisis, sanctions, inflation), the mall is suffering serious losses. And now the first abandoned, unfinished malls are appearing in the Moscow suburbs, and we may subsequently see a wave of closures of such centres for shopping and cultural leisure. This dependence of malls on the economic situation and its collisions one can metaphorically describe as a software bug, permanent glitch. The activities of malls are highly dependent on the wellbeing and prosperity of the emerging “middle class”. In connection with the most recent economic events (crisis, sanctions, inflation), the mall is suffering serious losses. And now the first abandoned, unfinished malls are appearing in the Moscow suburbs, and we may subsequently see a wave of closures of such centres for shopping and cultural leisure. This dependence of malls on the economic situation and its collisions one can metaphorically describe as a software bug, permanent glitch. Pavel Otdelnov |

Pavel Otdelnov. Mall #1. 2015, oil on canvas, 180x260. Private collection

Pavel Otdelnov. Mall #2, 2015. oil on canvas, 160x230. Private collection

Pavel Otdelnov. Mall #3. 2015, oil on canvas, 160x230. Private collection

Pavel Otdelnov. Mall #4. 2015, oil on canvas, 160x230. Private collection

Pavel Otdelnov. Mall #5. 2015, oil on canvas, 160x300

Pavel Otdelnov. Mall #6. 2015, oil on canvas, 150x200. Private collection

Pavel Otdelnov. Mall #7. 2015, oil on canvas, 150x200. The State Tretyakov Gallery

Pavel Otdelnov. Mall #8. 2015, oil on canvas, 150x200. Private collection

Pavel Otdelnov. Mall #9. 2015, oil on canvas, 150x200. Private collection

Pavel Otdelnov. Mall #10. 2015, oil on canvas, 160x230. Private collection, St. Petersburg

Pavel Otdelnov. Mall. Interior. 2015, oil on canvas, 180x260. Private collection

Pavel Otdelnov. "Mall. LEGO", 2015 oil on canvas, 130x180. Private collection, St. Petersburg

Pavel Otdelnov. Landscape with the yellow fence. 2016 oil on canvas 100x150. Private collection, Barcelona

Pavel Otdelnov. Installation "Mall. Glitch", the exhibition "Piece of Space Traversed by Mind" The New Wing of the Gogol Museum, Moscow

The installation view

The installation view

|

In the late 1950s-early 1960s Yury Pimenov, who had until then created canonical images of the industrial landscape of the 1920s (You give heavy industry! ) and Stalinist glamour (New Moscow ), painted several canvases to inaugurate the birth of a new urban environment. The District of Tomorrow, Marriage on the Streets of Tomorrow, The First Fashion Ladies of the New District glorify Khrushchev’s new prefabricated residential districts, against the backdrop of a sky blackened by the gib arms of building cranes and the stacks of concrete pipes on which they run sportily on their heels in brightly fluttering dresses, future husband and wife, parading directly on wooden bridges laid down in the dirt. At exactly the same time Dmitry Shostakovich was writing his own operetta Moscow.Cheremushki , which was shortly thereafter adapted in a screen version, glorifying the new housing developments as an opportunity to break away from the musty old world of communal flats to a new life — ascetic, free (the so-called “Khrushchevka” flats ensured privacy), desperately young, modern and even international. In Herbert Rappoport’s musical (born in Vienna and until his emigration to the USSR in 1936 the former assistant of Georg Pabst with whom he had worked in Germany and in Hollywood), they parody West Side Story and dance rock and roll directly on the panel of the house being built suspended on the crane. In the case of Shostakovich, Pimenov and Rappoport, people from the first avant-garde generation, the new housing developments of the thaw era marked a return to modernism, an appeal not to the mythical past or the eternal present as in the Stalinist Empire style, but rather to the future, at the time mentioned in the names of Pimenov’s canvases - Tomorrow , a time that has still not arrived, but will definitely come — so that one can for the time being endure patiently temporary inconveniences, the chaos of the establishment of the new and the dirt, which is presented in Pimenov’s pictures as sign of the organic vitality of the new world being built. The romantic halo that surrounded the new developments in the thaw years had definitively melted away by the onset of the stagnation era of Brezhnev. The typical suburban high-rise buildings became a standard form of alienation — whether it be the surprisingly depressing romantic comedy The Irony of Fate as the country’s main New Year story, or the desperately existential drama Vacation in September, or the paintings of domestic photo realists, who sought incidentally, through “branded”, “western” picturesque textures, to transform the “Russian distemper” into something akin to “English spleen”. In principle, the high rises of the Khrushchev-Brezhnev eras deserved the fate of the Pruitt-Igoe residential complex in Saint Louis that was so similar to them. The high-rises built in 1956 were transformed from a rational utopia into ghetto housing that was so uninhabitable that they were blown up in 1972. As we know, for American architect and art historian Charles Jencks this was the date of the death of modernism and the birth of post-modernism in architecture. In the case of Pavel Otdelnov, who has already studied for several years in his paintings the aesthetics of Moscow’s commuter districts, post-Soviet post-modernism in architecture, if there has been any, is represented not by Luzhkov’s towers, but rather by the shopping centres in suburbs, growing in amongst perennial Brezhnev residential districts and waste lands. Following the appearance of these structures in the typically grey architectural landscape, at least some colours have appeared. The acidic, eye-grabbing colours of the shopping centres turn them into mock buildings, and even giant toys. The bright local colours introduced in the architecture might also have inspired the authors of De Stijl to come up with Montessori educational toys. However, naturally there are no didactic aspirations in the toy nature of |

Moscow’s suburban moles. It is highly likely that the builders, who had decided to do something appealing to visitors, had been overcome by the same babbling and obsequious tone as advertisers and the compilers of menus, who abused diminutives, appealing to our infantile nature.Incidentally, in Pavel Otdelnov’s canvases, the shopping centre are devoid of people — their interiors are reminiscent of neglected space stations of unknown civilisations, while their multicoloured 3D boxes on stale wastelands rendered them more similar to huge sculptures than buildings that you can climb into. In the new cycle they definitively devolve into mirages. There are no longer any buildings — the inappropriately bright colours stand out in the primordial greyness of suburbs as a glitch, a digital malfunction, a suspended “matrix”. At the time of their disappearance, these phantoms looks particularly resplendent — laser shows, the gaudy fairy show of Las Vegas. However, they are so ephemeral that they are not even reflected in the eternal puddles of the suburban wastelands. In the case of Pavel Otdelnov, who has already studied for several years in his paintings the aesthetics of Moscow’s commuter districts, post-Soviet post-modernism in architecture, if there has been any, is represented not by Luzhkov’s towers, but rather by the shopping centres in suburbs, growing in amongst perennial Brezhnev residential districts and waste lands. Following the appearance of these structures in the typically grey architectural landscape, at least some colours have appeared. The acidic, eye-grabbing colours of the shopping centres turn them into mock buildings, and even giant toys. The bright local colours introduced in the architecture might also have inspired the authors of De Stijl to come up with Montessori educational toys. However, naturally there are no didactic aspirations in the toy nature of Moscow’s suburban moles. It is highly likely that the builders, who had decided to do something appealing to visitors, had been overcome by the same babbling and obsequious tone as advertisers and the compilers of menus, who abused diminutives, appealing to our infantile nature. Incidentally, in Pavel Otdelnov’s canvases, the shopping centre are devoid of people — their interiors are reminiscent of neglected space stations of unknown civilisations, while their multicoloured 3D boxes on stale wastelands rendered them more similar to huge sculptures than buildings that you can climb into. In the new cycle they definitively devolve into mirages. There are no longer any buildings — the inappropriately bright colours stand out in the primordial greyness of suburbs as a glitch, a digital malfunction, a suspended “matrix”. At the time of their disappearance, these phantoms looks particularly resplendent — laser shows, the gaudy fairy show of Las Vegas. However, they are so ephemeral that they are not even reflected in the eternal puddles of the suburban wastelands. Pavel Otdelnov’s new project would appear extremely topical today when the joys of the consumer society and hopes for some cultivation of the local social and living space are bursting like soap bubbles. Carefree post-modernism did not come to pass. The motley cubes of the toy buildings remain like a computer model imposed on the colourless landscape of the commuter districts, which have not stirred from their sleep, on waste lands built by the fortresses of the residential districts, which have not turned into cities, while the slush waits in vain for the tomorrow that will transform it into a street. Furthermore, it transpires that new technologies or state-of-the-art trends do not provide the most appropriate language to describe this reality: rather, it is the figurative art that Pavel Otdelnov studied at V. Surikov Moscow State Academy Art Institute, at the studio of one of the founding fathers of Pavel Nikonov’s “austere style”. Irina Kulik |

The project of installation in public space. Video made with the support of V-A-C foundation. Author of visualisation Patrick Moran