One early morning I happened to stay around a large train station. I might be waiting for the subway to open, or be waiting for a departure — I cannot quite recall. It was freezing cold outside, dark and drab, so I decided to kill the time in a station café. I got myself a dixie-cup tea and went on to look for a place to seat. Everything was occupied by other people waiting or napping, large luggage, and I had to land near two men of different ages who were engaged in a lively conversation. Apparently, they just met right there and then, and had already fixed something to tank up. Both were, most likely, making a transit connection. As I joined their table, there was a protracted silence that seemed to drag on forever. The conversation could not continue given my presence, and a new subject was in order. Then the older guy looked around the table and said: “So we are all going to part ways now. You’ll head your way, I’ll go to (he mumbled an unknown destination). This one (he pointed at me) goes someplace else.”The stranger looked around the table once again and held a pause. “Wherever, everywhere it’s the same sh*t all over!..”

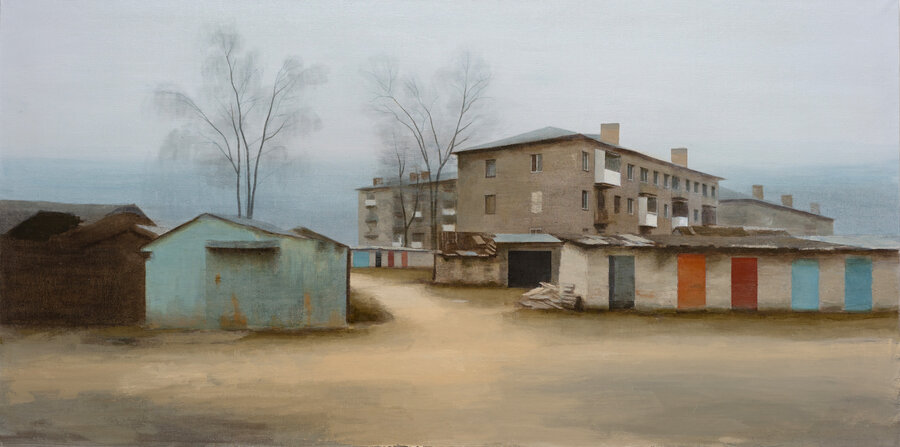

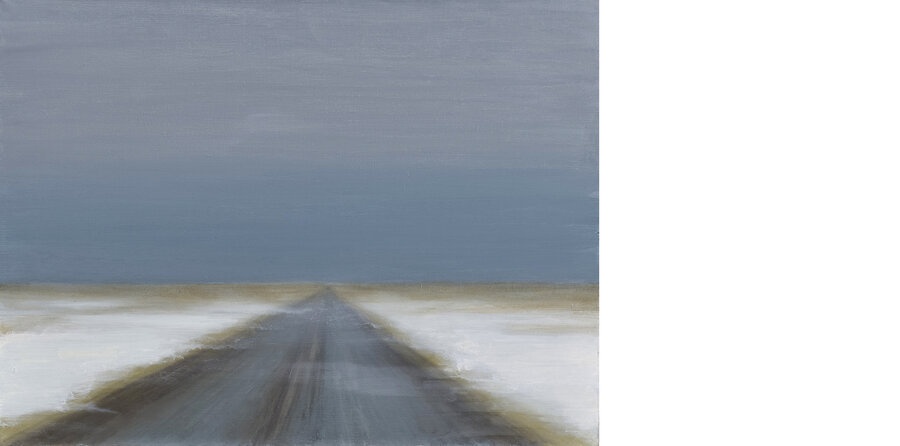

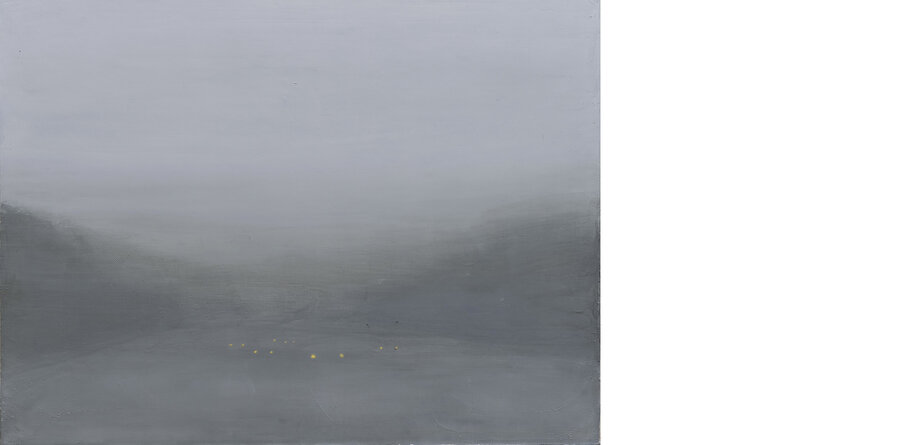

| I would like to revisit my reflections on nonsites that I began in Inner Degunino and Mall. Both series were informed by direct observation of the changing landscapes on the outskirts of major cities. The new project that I started during lockdown deals with virtual images. As captured by Yandex and Google streetview cars, landscapes are completely devoid of any idealization or an author’s view. These pictures have no author or author’s attitude towards the seen: the lens of an automated camera is perfectly impartial and disengaged. I based by paintings on the most banal and typical images that could be made anywhere in Russia. During lockdown, I had enough time on my hands to browse through many cities of our extensive nation and see their unretouched side as well. My previous series were an attempt to represent the changing cityscape as it could be depicted in a timelapse (Inner Degunino) or a search for a vantage point located in an imagined future (Mall). The new project turns to the disinterested machine vision, which does not differentiate between the surface of Mars and a hometown street. A new generation of people has emerged over the recent few years who rely on the surrounding post-Soviet landscape for self-identification. Arguably, there is a trend among people born in the 1990s to romanticize the Soviet past and its attributes. A recent coinage even terms it as the Lapenko Phenomenon. A great many subscribers follow such social media communities as The Beauty Of Blight, Birch Tree, Russian Death, Outskirts, Any Russian City, Each New Day Is Brighter Than The Other, etc. These communities make numerous daily posts, mostly of photos with extremely mundane landscapes. Each such picture generates active |

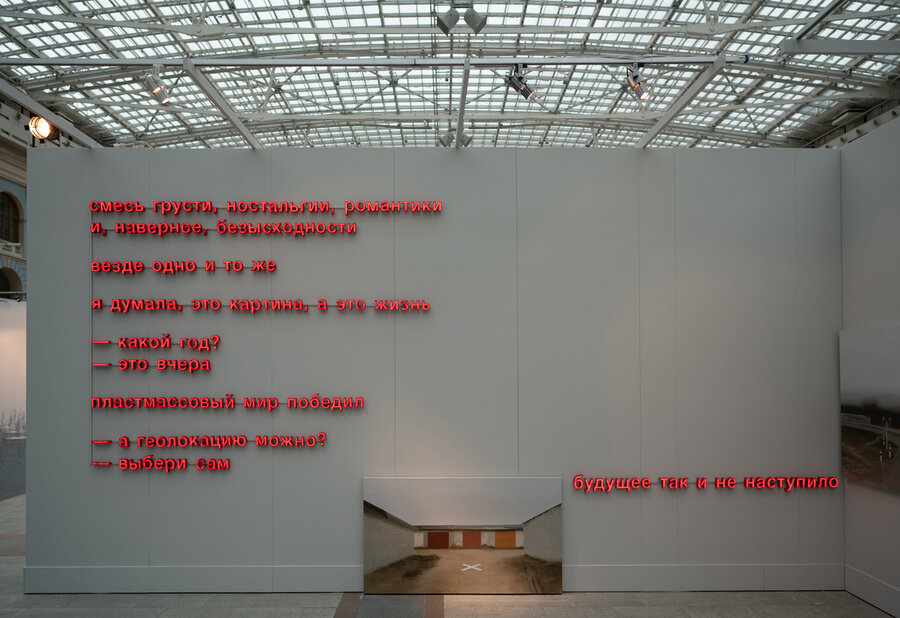

discussion, making the comment section into a competition of wits. Certain phrases are spammed repeatedly, and popular jokes are memed. I think these repeated comments are quite telling — they provide an insight into the younger generation's outlook on the surrounding landscape. It is both an attempt to romanticize the place of own existence, aesthetically conceptualize and accept it, and an attempt to build an ironic distance, find a personal point of view. The landscapes that resulted from my virtual walks are exhibited alongside the social media comments. I have transformed them into neon signs, like Garage or Groceries, their shape and lettering hinting at the reality that actually underlies these phrases. I planted them into real-life landscapes and made a short series of photographs. The social media comments, directed towards the surrounding environment, have thus incorporated themselves into this reality. The video Prayer was filmed on the outskirts of Moscow, where a residential project is in development in the flood plain of the Skhodnya River. To protest the development, a local activist dug out huge letters in the ground, so big as to be clearly seen on Google satellite images: Putin, save Skhodnya. However, a high-rise residential project was soon built right on top of the letters. Disillusioned with the government, that same activist dug out a new message nearby, now appealing to a higher authority: God save Russia. These letters, similar to the glowing neon comments placed in real-life landscapes and attributed to no author, sound like an utterance by earth itself |

Pavel Otdelnov. Nowhere. Concrete fence. 2020. oil on canvas. 100x200. Private collection

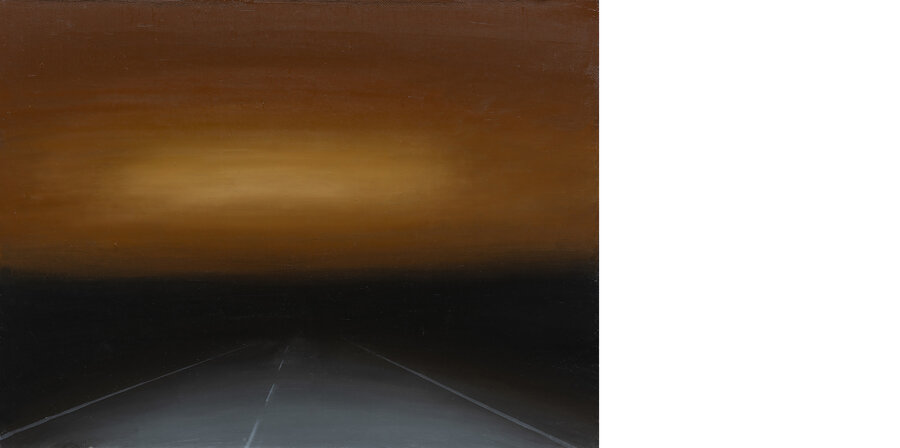

Pavel Otdelnov. Future. 2021. oil on canvas. 45×60. Private collection

Pavel Otdelnov. Nowhere. Enthusiasts street. 2020. oil on canvas. 100x200

Pavel Otdelnov. Nowhere. Blockhouses. 2020. oil on canvas. 100x200. Private collection

Pavel Otdelnov. Nowhere. Sheds. 2021. oil on canvas. 100x200. Private collection

Pavel Otdelnov. Nowhere. Scrap-metal. 2020. oil on canvas. 100x200. Private collection

Pavel Otdelnov. Nowhere. Red barn. 2020. oil on canvas. 100x200

Pavel Otdelnov. Nowhere. Puddle. 2020. oil on canvas. 100x200. Private collection

Pavel Otdelnov. Nowhere. Stander. 2020. oil on canvas. 100x200

Pavel Otdelnov. Nowhere. Yellow tube. 2020. oil on canvas. 100x200

Pavel Otdelnov. Nowhere. Concrete blocks. 2020. oil on canvas. 100x200

Pavel Otdelnov. Nowhere. Green fence. 2020. oil on canvas. 100x200

Pavel Otdelnov. Nowhere. Overpass. 2020. oil on canvas. 100x200

Pavel Otdelnov. White Landscape. 2020. oil on canvas. 60х90. Private collection

Pavel Otdelnov. Gray Landscape. 2020. oil on canvas. 60х90. Private collection

Pavel Otdelnov. Yellow Landscape. 2020. oil on canvas. 60х90. Private collection

Pavel Otdelnov. Black Landscape. 2020. oil on canvas. 60х90. Private collection

Pavel Otdelnov. Globality. 2019. oil on canvas. 150х200

Pavel Otdelnov. There is no aesthetic in it. 2021. oil on canvas 180x260

Pavel Otdelnov. Garages. 2020. oil on canvas. 100х150. Private collection

Pavel Otdelnov. Garages. 2020. oil on canvas. 90х160. Private collection

Pavel Otdelnov. Garages. Panorama. 2020. oil on canvas. 115х345

Pavel Otdelnov. Zhuten. 2020. oil on canvas. 115х345

Pavel Otdelnov. "— Can you send the location? — Pick it yourself" on Cosmoscow Art Fair. 2020

Pavel Otdelnov. "— Geolocation, please? — Choose yourself" on Cosmoscow Art Fair. 2020

Pavel Otdelnov. First off, it is beautiful. 2020. Installation, photo

Pavel Otdelnov. — Can you send the location? — Pick it yourself. 2020. Installation, photo

Pavel Otdelnov. — What year? — It's yesterday. 2020. Installation, photo

Pavel Otdelnov. It's the same everywhere. 2020. Installation, photo

Pavel Otdelnov. There is no aesthetic in it. 2020. Installation, photo

Pavel Otdelnov. The Land of Fascinating Wonder. 2020. Installation.

The message God save Russia near Mitino District was dug up by Andrey Finonchenko, a Skhodnya local. It took him two months to complete. This is the second large-scale wording he has done. The first one said Putin, save Skhodnya. This was Andrey’s way to protest development in the water conservation area of the Skhodnya River. Nonetheless, major construction began less than 12 months later right on top of the first message. It is now a new residential project. Disillusioned after the first attempt, he decided to appeal to a higher authority.

Pavel Otdelnov. Prayer. 2020. video. 2' 41"

| Pavel Otdelnov’s projects focus on urban locations that attract little to no attention — most people, if they happen to go there, try to leave as soon as possible. This might be former industrial sites that have lost some of their function or been repurposed entirely, parking garages, warehouses — all such places are located on the outskirts of the city and mark its abrupt termination, a cliff with nothing but an endless landscape over its edge. The new exhibition by Pavel Otdelnov, Russian Nowhere continues his analysis of these spaces. The subject matter comprises places, which he discovered when browsing online maps, and social media comments. Otdelnov’s practice is in artistic exploration, mostly through painting. Each new iteration, however, taps new media which enables the artist to expand the boundaries and widen the angle of view on the problems considered. In his most recent large project Promzona (2019), Otdelnov employed storytelling, documentary video, found-object installations and even smells that all came together into a wholistic multi-layered body, |

addressing the meanings of history and postmemory as well as representation of space. In the Russian Nowhere series, the artist continues to actively engage with text: he transforms snippets of text found online into light installations, reminiscent of a corner store sign, and then incorporates these quotations into real-life landscapes through photography. The resulting effect is defamiliarisation. Pavel Otdelnov is aware that direct replication of reality is impossible, so he uses different optics — machine vision and collective human intelligence. This typifies his work as postconceptualism. Turning to landscapes that are no longer utilised or populated, the artist reaffirms their existence and proposes to give them a negative definition. These places exist but their description or identification, even supported by an accurate image, is not possible. This “nowhere” is actually everywhere, emerging from the void, which is, in fact, the main character in Otdelnov’s work. Marina Bobyleva |

|

The new exhibition by Pavel Otdelnov, symbolically titled Russian Nowhere, makes a mesmerising impression, in a way evocative of David Lynch movies. Trying to articulate its aftereffect on the viewer, which does not quite lend itself to verbalisation, it can be argued that the “enigmatic landscapes”1 on display are a paradoxical combination of extreme defamiliarisation and materiality, on the one hand, and superhuman tenderness that ventures into mysticism, on the other. The new series by the artist revisits the subject of “non-places”2 and continues the deep exploration of our collective unconscious by focusing on urban marginalia. This time, however, the poetics of non-places is enriched by an infusion of virtual imagery. The term “non-place” was originally coined in art criticism by the founder of land art Robert Smithson, and it has been used to denote the zones, produced by the urban civilisation, that are occupied for short periods of time and anonymously, and that erase personal identity. In philosophy, as introduced by Michel Foucault, such places are termed “heterotopia”, from the Ancient Greek for “other” and “place”. A place is identified here through a differentiating, special mode of life and a special chronotope. Endless casemates of garages, deserted highways going nowhere, industrial estates, road junctions and other “disowned spaces” in the urban outskirts of Russian Nowhere — all that can await us around any corner in our familiar daily routes (“I thought it was a painting, but this is life”) — these are examples of heterotopias with their particular aesthetic and space-time configuration. The heterotopias / non-places in Pavel Otdelnov’s new series are so well known to everybody who lives in Russia that they unfailingly produce an effect of stark déjà vu, which reveals the eternally Russian “it’s the same everywhere”. Back in 1951, at a Darmstadt conference, Martin Heidegger made a presentation “Building, Dwelling, Thinking” on a bridge construction project, where he argued that the identity of a place emerged from both its objective spatial parameters and from the eye of the beholder. When presented with the heterotopias in Pavel Otdelnov’s new series, the question of that eye immediately comes to mind, which can, once answered, serve as the key to the world of Russian Nowhere. The seminal question posed by Michael Foucault “who is speaking?”, as applied to visual arts, should be restated as “who is looking?” Whereas the past series by Pavel Otdelnov offered a most sympathetic view on the depicted non-places that can be attributed as a view of a person in the future3, in case of Russian Nowhere such perspective is no longer possible: Enthusiasts Street now leads nowhere, and the monolith concrete fence spanning over the entire horizon bears the inscription: “The future has never come”. In Russian Nowhere, Pavel Otdelnov has aptly captured this recently emergent phenomenon in the collective sensibility of dealing with the loss of the future as a human project. A person is not a personal project anymore, the person has now denounced the myths, which used to hold power over us, of being the architects of our own futures. The initiative now lies with non-human actors: the natural entropy that prevails and erases from the face of the earth the remains of grand social utopias, the onslaught of new deadly viruses brought about by the environmental disaster, the menacing self-animation of technology. Even if the future were to present itself today, this would be through personalised eschatology (“Russia is the land of fascinating wonder: Start your life here, and it all goes under”). So whose eye is it, contemplating the dehumanised space with such |

defamiliarisation and distance as if from a bird’s eye view? Might this be a machine eye? Indeed, the optics used in Russian Nowhere is on principle that of a machine: both in the photographs and in the paintings of this series, there is no need for human presence in the landscapes captured by dispassionate machine vision. The artistic gesture — newly introduced here by the author and amplifying the already existing defamiliarisation effect — consists in painting the canvases from images found on street view by Yandex and Google, and in recreating a painterly image from that; this takes to the extreme the themes of dehumanisation of the depicted space and of the subject’s death in art. The artist himself calls this technique the “principle of simulated remote view”. If this is a machine looking, though, why do we get a persistent anxious apprehension from these landscapes, as if something unseen is lurking behind the seen, as if something has happened or is just about to? Why the presence of vibrating sadness, piercing nostalgia, phantom pains over the era long gone and the man dissolved in these dehumanised landscapes? Over the paintings missing the shadows of people once living, building, dreaming here, whose dreams were turned to dust and faded into oblivion. Or over those who, continuing to dwell in the drab non-places, in the dimensionless faceless spaces of the Soviet (Russian?) Atlantis, which is submerging underground and under tonnes of compressed time right before our eyes, are also becoming invisible, turning on Otdelnov’s canvases into barely distinguishable marks, an empty sign of a person, a ghost. This is no human view: a person in the space of Russian Nowhere is dematerialised (their palpable absence gives a powerful impetus to imagination). Neither is the view that of a machine. Machines have no nostalgia, and the world does not present itself to them as presence. Still, whose eye could be looking at the lands in Pavel Otdelnov’s Nowhere? The one looking at these monotonous, almost fully devoid of colour, literally in-congruous landscapes (“there is no aesthetic in it”) could be one of the Wim Wenders’s angels from Wings of Desire (1987), Cassiel, whose original purpose was to observe, witness and keep record of reality. Or Wenders’s other angel, Damiel, who is sympathetic to the people on earth and appreciates this flawed world so much that he becomes willing to give up his immortality in order to see it through the mortal’s eyes or, say, experience a “mixture of sadness, nostalgia, romanticism and, probably, hopelessness”, as relayed in one of the anonymous sentiments that Pavel Otdelnov has retrieved literally from our collective unconscious — from the social media. His series of photographs is poetic in its precise use of verbatim quotations from recurring comments in social media communities focused on the “aesthetic of gloomy nowhere”, or, to cut through the euphemisms, on the ruination of Russia4. Ruins are definitely featured among the repetitive structures in Pavel Otdenov’s work. In his artistic world, ruins are not so much a representation of past events as, rather, a hint at the impossibility of such representation, at the contained isolation of past experience from us. Although its progressively disappearing traces are still present, the past is not meaningfully perceived by us, which makes it simultaneously horrific and alluring. Yet, taking a different angle, the non-places — that, despite of all of the above, Pavel Otdelnov makes us admire by virtue of the magical power of art — might be that last haven where the vestiges of humanity can find rescue from the glossy terror of simulated reality. And where amidst the voiceless deserted middle of nowhere, with its invariably grey skies and washed-out lighting, it is the only remaining place to, perhaps, encounter an angel. Svetlana Polyakova |

1 Zatsepin K. A. “Enigmatichesky Peizazh” [Enigmatic Landscape] // Prostranstvo Vzglyada. Iskusstvo 2000–2010kh Godov [The Space of Vision. Art of the 2000–2010s]. In Russian. Collection of essays. Samara: Knizhnoe Izdatelstvo, 2016

2 Editor’s note: as used in several humanitarian disciplines, the term “nonplace” has different forms in both Russian and English. The variant “nonplace” is typical of Robert Smithson’s artistic concept, which is discussed further in the text, typical of culturology (e.g., see Symbolic Exchange and Death by Jean Baudrillard), and of anthropology (e.g., see Non-Places: Introduction to an Anthropology of Supermodernity by Marc Augé). Another variant, “nonplace”, is current in studies of utopias and in urban studies (e.g., Yury Saprykin’s writings). Note, however, that the Russian academic and journalistic discourse is yet to settle on an established usage on this term, and it may have different meanings depending on the context.

3 See Polyakova S.V. “Ne-mesto v Iskusstve i v Postchelovecheskom Mire” [Non-place in Art and in the Post-Human World] // Dialog Iskusstv [Dialogue of Arts]. In Russian. 2017. No. 4.

4 The phrases used in these works take on an additional layer of meaning when one learns that the red lettering was made to order by the same company that manufactures signs for such outskirt regulars as construction supply markets or Pyaterochka, a value grocery chain.